|

| Shieldwall is a must-pack for this summer's holidays: beach or not |

Tuesday, July 3, 2012

Monday, June 11, 2012

How to Write a Medieval Novel: Eat Like a King

One of the tricks of convincing fiction of any period is to

get all the little details right. Top of

the most neglected things in writing is things like toilets, food, and personal

hygiene.

While it’s probably hard to bring across medieval smells,

and as many of these smells would seem ‘normal’ do you want to be drawing

attention to them all the time? Probably

not, but one thing that’s good and fairly easy to get in is food and the

delights of the table.

|

| Stews and kebabs are a simple, and timeless way of cooking meat. Here a scene from the Bayeux Tapestry |

Our modern dinner table with metal knives, forks spoons and

china plates are a surprisingly modern invention, but what would a medieval

table look like? This of course depends

on when exactly you’re setting your story, and there are some important moments

to think of. Most people ate with a

spoon, knife and fingers. Forks didn’t

come into fashion until Richard II, who was also supposed to have brought in

the handkerchief, and who also inspired the first English cookbook: Curye onInglysch, which covers dishes like Malaches, Raphioles, Crustardes of flessh.

Want to try these meals?

Well, there are a number of places where you can pick up medieval

recipes for all kinds of dishes: from the royal to the everyday. While there are a number of places that allow

you to dress up and feast in right royal medieval style, it’s takes a little

more work to eat like a peasant.

Peasant food is of course a tad more timeless. But it’s not hard to make rye bread, sour dour

bread, flat breads. Or even sample curds

and whey, and many other staples that we no longer eat.

Until about 150 years ago, most people in England used

wooden bowls and plates for eating. Wood

turning was one of the ubiquitous industries you would find throughout Europe –

and, like parish and shire boundaries - these wood turning workshops have

changed little in the last 1000 years. The

last wood turner, George Lailey, died within living memory, in 1958.

|

| A simple peasant meal: circa 2012 |

I’ve blogged about this before, but its worth repeating a little

here: of how Lailey’s hut was almost exactly like Anglo Saxon grubenhaus. As Morton said,

'[he] turns bowls exactly as they did in the days of Alfred the Great... to say that eight hundred years seemed to have stopped at the door conveys nothing. The room was an Anglo-Saxon workshop! The floor was deep in soft elm shavings, and across the hut was bent a young alder sapling connected to a primitive lathe by a leather thong.'

While he was the turner, like many other arts, this one has been revived. I managed to get a bowl and a plate from RobinWood, 2009’s Artisan of the Year. Add in a horn spoon, some pottage or curds, and you have a real life re-enactment.

'[he] turns bowls exactly as they did in the days of Alfred the Great... to say that eight hundred years seemed to have stopped at the door conveys nothing. The room was an Anglo-Saxon workshop! The floor was deep in soft elm shavings, and across the hut was bent a young alder sapling connected to a primitive lathe by a leather thong.'

While he was the turner, like many other arts, this one has been revived. I managed to get a bowl and a plate from RobinWood, 2009’s Artisan of the Year. Add in a horn spoon, some pottage or curds, and you have a real life re-enactment.

Mine’s about 5 years old.

It gets used every day for lunch, and while I bake my bread in an oven,

not by the side of the fire, it’s fairly easy to replicate many ways of

cooking.

Labels:

food,

George Lailey,

grubenhaus,

How to write a medieval novel

Thursday, May 10, 2012

How to Write a Medieval Novel: a practical guide no. 2

So! you're characters are riding through the countryside, or they come out of their doorways - and.... what do they see?

Good stories, where ever they're set need worlds that are believable and often it's the variety and authenticity of the little details that really lift historical fiction, and give the reader the illusion that they've immersed themselves in a real world in all its facets: with farmers, clerics, travellers, pilgrims, knights or huscarls all mingling in a way that feels real.

Of course no one has been to the Middle Ages, so how do you bring this level of detail to your story?

The written sources tend to be a little bland on these little everyday details for almost any period because chroniclers don't see much noteworthy in the 'everyday.'

There are a few places where you can find these details. Aelfric's Colloquys are a good example. Fancy catching a whale today lads?! Check out Ann E. Watkin's translation here

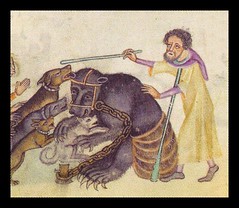

But luckily the monks who illustrated thier texts seem to have had a penchant for putting the everyday in the margins of the holy, profound, sacred and heroic texts they were illustrating.

Wednesday, May 9, 2012

Have you liked Shieldwall yet?

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Shieldwall-Justin-Hill/dp/0349123373/ref=tmm_pap_title_0?ie=UTF8&qid=1315579893&sr=1-2

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

How to write a Medieval Novel: a practical guide no. 1

The Dark Ages?! Not at all. As I'm doing all this again, I thought I would list the things I've found useful in creating a convincing medieval setting.

1. The literature. Duh! In some ways there's nothing better than what contemporaries wrote about the world they lived in. For an Anglo Saxon setting this left me a little stumped, as anyone who's read any Anglo Saxon poetry, knows that the Anglo Saxons lived in a permanent winter, amidst ruins, and lamenting the fate that led them to exile/lordlessness etc. I was left a little stumped, because I couldn't have a novel set in a permanent midwinter. But then I came across this book, The Lost Literature of Medieval England, in the corner of Lingnan University library, which had last been taken out in 1962. A fabulous read, it also introduced me to the corpus of Anglo Saxon literature written in Latin, which composes of hagiographies, which are the opposite of the poetry, in that they chronicle how saints turned cold wilderness into flowering fields full of birds and bounty.

Bingo! I now had contemporary sources chronicling both their of summer and winter.

But of course it's not so straightforward, as writers often wrote because they had ulterior motives. Richard Fletcher is very good in The Barbarian Conversions, in teasing the religious accounts of conversions, where Saint A turned up at pagan site Z, chopped down their sacred oak, and then the people were amazed and accepted Christ. He asks the kind of questions any serious writer should ask: what exactly did that mean? How well did people understand what they were accepting. How much did older beliefs survive and continue in different forms. I find it's always good to remember that just because people lived in a less enlightened age, they were not necessarily any more or less daft than people now. And in many ways their concerns might prove surprisingly similar to worries now.

Take the Anglo Saxon charms, for example. Often they say put a poultice on and say a certain prayer or charm three times. Now the simple reading would be that they believed in the power of mystical charms. Or - and perhaps a more practical and interesting explanation is that the repeating the charm five times took a certain and appropriate amount of time. Something of an ancient egg charmer.

Monday, April 30, 2012

Edmund Said, Orientalism, and how writing has changed now writers use computers not paper

I was never a big fan of Edward Said's Orientalism, and the limited way it seemed to focus views of the east, but found this podcast very interesting. Great Lives, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01gvn2k

Straight after that I stumbled across this BBC documentary, which was also fascinating. Do writers write differently on paper? Fay Weldon thinks so. From April 2011. subscribe to the podcast http://www.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/series/r4choice Tales from the Digital Archive

Sunday, April 22, 2012

Shieldwall: Top of the Paperbacks, Sunday Times April 22nd

Shieldwall picked as of the week's paperbacks:

'In the early 11th century, England is close to anarchy.... When Ethelred dies and the raiders from the north arrive, Edmund and Godwin become the standard-bearers of native resistance. With supple, intelligent prose, Hill not only succeeds in bringing this distant world to life but, in Godwin, has created a complex character whose struggles to be true to his ideas of duty and friendship are entirely convincing.'

Nick Rennison

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

Literary Festivals: the magic ingredients

Gatherings of writers can be odd events where egos and insecutirites make a toxic mix. But at their best they are creative and compelling meetings of minds and ideas.

How to nuture this mix?

Literary festivals have been on my mind recently, having just been to a few, and as we start to look forward to the 2012 Hong Kong International Literary Festival.

One question is who or what is the festival for? If it is for the audience then I think that they feel a little flat for the writers. They turn up and meet an audience, say the same old things about a book they finished possible one or two years before, at best, and then they 'come down' with a slice of cake and a cup of tea: and then head home.

If that's what you're offering the writers, then I think you're missing out. And certainly writers will pass on the lack of enthusiasm they have for that event.

One simple way festivals seem to approach this is in the name. Literary festivals tend towards the static interaction; 'writer's festivals' tend towards something more interactive and stimulating. This can be workshops; more informal gatherings; literary walks; and of course - hanging out in the pub with writers - which is probably the favourite part for most writers where their audience can talk back to them.

You see - writ

ing is a really odd art form - where, uniquely, the artist never meets their audience, and perhaps the creation is divided from the experience of that art by years or decades, and thousands of miles.

I sit alone in a room and write, and then after an unknown period of time and space, another person sits alone in a room and reads my books. And most of the time I have no idea what they liked or didn't like about the book. Or what questions and responses they had etc.

So what does make a literary festival?

Centralised locations: where people can hang out between and after events. Where there is a buzz, a unique place where story and the written word are for once taken out of the normal world and celebrated. This can be the tent square of Edinburgh or the bar/restaurent of the Beijing Bookworm.

The audience speaks back: breaking down the barriers, so that writers are not just talking to audiences. In Chengdu, for example, I visited a school for disadvantaged children, many of whom had lost parents in the earthquake. And although I was there to talk about writing and my experiences in China, it is impossible to talk to young adults who have come so far in their lives, and not be affected. That's an audience a writer does not forget.

Stimulating: everywhere that has a festival has something special about it. This should be brought into the festival. An obvious example is the Ubud Literary Festival in Bali, where the culture is brought into the festival in food, music and setting. But it's almost unimportant - as long as there is a conversation between place, writers and people.

Authors: interesting authors are a must. That's a duh!

And Audiences: harder to control of course, but places with interesting audiences make for much more stimulating places to visit. Because, we come back to the point, I think: that good literary festivals should be a conversation between writer, audience and place. And not a one way conversation.

Sunday, March 25, 2012

Bookmarks

I like bookmarks. Being a nerd, I even have specific bookmarks for special books.

The obvious one is an embroidered silk bookmark i got to commemorate the pope's visit to England in the 1980s. What can I say: I was raised Catholic and I was an altar boy, and if you played Dungeons and Dragons despite a papal ban, you had to do something to mitigate your sins.

I got a set of sandalwood ones when I first went to China, and they mark favourite poems in my favourite anthology.

And then I was reading The Two Towers recently and I came across this. It's a plain piece of blue card, faded to brown across the top, where it has at some time stuck up from the top of the book. And it contains a list of names, written in my brother's handwriting with a sharp, probably a H or 2H pencil.

And it was written some time between 1981 and 1992.

I'm guessing at the reason why there is a list of names here. But I'd say it is my brother looking for the name of a character.

That's the basic information, but what seems more worthy of a blog post is the effect it had on me: I wanted to know who or what all these names described. If anyone knows please do let me know. I know they mean something....

Dorathon

Dorathan

Dargonath

Doranor

Doramir

Dorondil

Dorthondor

Dorongil

Dorthon

Thursday, March 22, 2012

Sunday, March 18, 2012

Chengdu: City of Beautiful Girls, Spicy Food and of course, Poets

It's interesting, as an author, to turn up to China's festivals, and feel the difference in the respective audiences.

It's interesting, as an author, to turn up to China's festivals, and feel the difference in the respective audiences. It's not just that the Chinese cities and provinces are different (they are - as different as London and Athens, for example) - but also that the foreigners attracted to the various places are different.

Shanghai attracts a high end audience. Well turned out, well educated, rich.

I was told Suzhou would be the wives of factory owners, and there were lots of those there, but I was there over St Patrick's Day, and all I saw was young people everywhere.

Beijing is probably my favourite, because it's full of Sinophiles.

But Chengdu is interesting, as it seems full of Old China Hands, Tibetologists, and Panda People. But what's striking about Chengdu is that Chengdu is a city of spicy food, beautiful girls and poets. And when you go to read there, the audience is going to be 2/3rds local Chinese.

Which is a little worrying when you're talking about Early Medieval English History. But there was no need to fear. A packed house, and a good half an hour afterwards answering extra questions and signing books.

Which is a little worrying when you're talking about Early Medieval English History. But there was no need to fear. A packed house, and a good half an hour afterwards answering extra questions and signing books. Great to see old faces still there! And thanks for the photographs!

Thursday, March 15, 2012

On Tour Again: Chengdu Book Worm Lit Fest

It was a grey day in Hong Kong: with low misty clouds, when i set off to Chengdu.

It's an odd feeling for me to fly into China. It feels in some ways like going back in time. It also feels like coming alive again, and when I landed the weather was pretty similar, though about 10 degrees colder.

I'm here for the Chengdu Bookworm Literary festival: one of my favourites. I was here last, four years ago, when Rob Gifford and I (apparently) argued spectacularly about the veracity of our stories. People are still talking about that night here.

The hotel is the same. The Kempinski: and you can tell how far china has moved on now in the quality of the hotel staff and hte reception you get at these places. Otherwise they're much the same. Pretty girls playing the piano in the lobby, men sipping tea, and men handing out hooker cards at the front door.

I spent the afternoon walking some back streets, and while much about china has changed, the back streets have not. The Chinese do cities well: they're cities that you walk around, they are cities on a human scale with all kinds of odd shops and activities happening on the pavement and in hte open doorways of shops, that double as houses, with people sitting in bed, with thick duvets pulled over their legs.

I was there for the launch night: a feast of speeches in Chinese and English, including a government spokesman, from the investment council of Sichuan province. Some things never change, and speeches are one of them. But I nipped out half way and went back to a little back street I found where there were on street restaurants: and sat on a rickety iron stool, and had yu xiang aubergine, pigs stomach and jia chang dofu.

The back to the Chengdu Bookworm and lit fests are best when the events are over and you get to talk to the people there. I like the folk at Chengdu: many of whom were the same and were kind enough to come along and say hi, and those who i had never met before.

Thursday, February 23, 2012

How being a nerd turned me into a writer

I ran into Liz and Mark over at My Favourite Books blog over the summer, when they ran a special feature on Vikings. Somehow Shieldwall slipped under their radar, but they were kind enough to take a copy, and review it: you can read Mark's thought here

I ran into Liz and Mark over at My Favourite Books blog over the summer, when they ran a special feature on Vikings. Somehow Shieldwall slipped under their radar, but they were kind enough to take a copy, and review it: you can read Mark's thought hereLooking through their blog I saw lots of the kind of books I like to read: Black Library for example, the publishing arm of Games Workshop, a company I've been a follower of since they started making lead figures I could use for Dungeons and Dragons, and then wargaming in general. And so we thought it would make an interesting blog to talk a little bit about something people don't usually admit to: being a nerd, and how it influences their writing.

I like these kind of pieces, because it forces a writer to analyse why and what they want to write. Check it out here

Monday, February 20, 2012

New Elizabethans: who will you vote for?! Tolkien, of course.

To mark the Diamond Jubilee, James Naughtie will be profiling the 60 public figures who have made the greatest impact in these islands during The Queen's reign - men and women who have defined the era and whose deeds will stand the test of time

So begins the radio 4 website's attempt to define the age within which we live through the lives not of the queen, but of her subjects.

Who then were the 'old Elizabethans'? Well the obvious name would be William Shakespeare. Though if you asked people then, he's unlikely to have been on the list. He stands for the theater and English literature and literacy, which was starting to combine in the theaters and in the romantic art of poetry.

Sir Walter Raleigh sums up the privateers and also the defeat of the Spanish Armada.

There is something symbolic in a process such as this. Figures are nominated not only on behalf of their own achievements, but also for what they symbolise about the society they have lived within.

On Start the Week of Monday, 13th February, a couple of interesting names came up. Richard Branson, to stand for business, and the curious world of marketing within which we live.

On Start the Week of Monday, 13th February, a couple of interesting names came up. Richard Branson, to stand for business, and the curious world of marketing within which we live. Nick Leeson, the man who broke Bearings Bank, was also suggested, as he symbolised the financial crises that have rocked out world.

I'm going to nominate another writer who's not only had a profound effect on my life, but also on the world within which we live. In fact, I'd go so far as to say he's had a greater effect on the modern world than any other writer, except perhaps Dickens. Yes, it's JRR Tolkien.

Why Tolkien? It might seem an odd claim for a writer whose work was largely linguistic and personal, and based on a neglected area of interest: mainly medieval sources (Beowulf, Gawain, Sir Orfeo, Sir Launfal) or fairy tales, which have been thought of as suitable only for children.

Tolkien's work has reclaimed fantasy - or faerie - from the Tinkabelle and Flower Faries. He has brought magic back into the mainstream. Look at the modern world: it's dominated by stories that revolve around the fantastic: Avatar, Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings films, computer games (the big business development of the last ten years), Game of Thrones. Much to the horror of established literary critics the passion people have for these kind of stories is not proving to be ephemeral and passing.

Tom Shippey goes into extensive and fascinating detail about Tolkien's affect 'Author of the Century' but this week I came across a few interesting facts about Tolkien, which show the depth and breadth of his affect on modern culture. Whole sections of bookshops are devoted to Fantasy writing, much of which owes it's inspiration to Tolkien.

Borges lamented the lack of 'epic' within English literature, but as Humphrey Carpenter, biographer of Tolkien, said: Tolkien brought saga and epic narratives back into English literature, from which they had been lacking.

Borges lamented the lack of 'epic' within English literature, but as Humphrey Carpenter, biographer of Tolkien, said: Tolkien brought saga and epic narratives back into English literature, from which they had been lacking. There's surely no other author who has inspired such a vast creative response to his work: from art to literature, and music, with albums like Sally Oldfield's Water Bearers obviously based on Tolkien, but Led Zepplin's work less obviously so. The list doesn't stop there, however. The Beetles were so struck by Tolkien's work that even they considered doing a film based on Lord of the Rings, with George Harrison as Gandalf, Paul McCartney as Frodo, Ringo as Sam and John Lennon as Gollum.

The list could go on, but the fact is, Tolkien's work has had a greater effect on the modern world than any other author. Hardly surprising considering the Lord of the Rings is the second best selling book of the 20th Century, beaten only by the Bible.

Friday, February 10, 2012

Reading the World, Hong Kong Book Fair 2012

Of course, no one in Hong Kong is interested in reading. Or books. Or that's what people think. And then you turn up to the Hong Kong Book Fair and rub shoulders with the million or so other visitors, and then you begin to wonder.

China, is of course the place where the written word has a special status. And its a rewarding experience to see the enthusiasm and the excitment that books can provoke among all ages.

Last year, I felt a little anachronistic, being scheduled to speak about a novel on Dark Age England, in Hong Kong, the brightest neon of the modern, overlit age. But I had a very solid 100 or so writers, of whom a handful were ex pats and the rest a fascinated audience of Hong Kongers and Mainlanders.

I've just had a meeting with the people running the Book Fair this year. The theme is 'Reading the World.' I think it's going to be a great event, and I look forward to walking round and feeling the passion of the readers around us.

Wednesday, February 8, 2012

The How and Why of Self Publishing 1

Publishing is going through all kinds of changes, and as a practicing writer, I'm looking at the opportunities as much as the problems. Actually, I'm convinced the challenges are more for the publishers and the legacy bookshops. There are more benefits for writers. Benefit no 1: backlists.

It's an odd feature of the way the publishing industry has developed that it's not cost effective to keep backlist books in print. This extends to rather crazy examples. My first novel, a multi prize winning portrait of modern China, won international acclaim and was picked by the Washington Post as a Best Book of 2001 - but when my editor left Weidenfelt and Nicolson, I did too, and ended up at Little, Brown.

This book, The Drink and Dream Teahouse sold 11,000 hardbacks in the first year in the UK and Commonwealth markets - and whenever I go to readings people always ask me where can they buy it?

On the back of this interest I nagged my editor to get this novel back into print, but was distinctly unwilling. Ebook? meh. Paperback. Ugh.

Bugger the lost of them, I thought, I'll publish the thing myself.

I've been interested in the business model of new publishing houses who are going with a combination of print on demand and ebooks. But it's sobering looking at the finances.

Tips from self-published authors included 'get yourself a professional looking cover.'

So to start off I approached a top UK cover designer who told me that publishing houses pay £800+ for book covers. No wonder, then that it doesn't make sense for mainstream publishers to publish back lists. And this gets me thinking about the insanity of the publishing process, where average author's advances have been in steady decline over the last decade. Andrew Lownie reported in 2006 that of the 27 books he sold, with an average advance of £52,592. By 2006 the average had dropped to £31,070. Advances have been falling ever since, with most advances under £5,000.

And of course, skim off all these figures, the 10-15% that goes to author agents.

Obviously there is money in publishing, because there are profitable publishers and booksellers and agents throughout the industry. But precious little of it filters down to the authors. This will change. In fact, its probably changing already.

It's a fairly simple equation. Cut out the middle men. Middle men here equals agents, publishers, and bookshops. Never before has it been so easy and practical to get books to the audience. That's the principal I'm following this year as I set off on the self publishing journey.

Monday, February 6, 2012

Index Cards and the Art of Writing

You collect your notes and jottings, but how to get those into your novel?

I collect my notes and write them down onto index cards. This can be quite a time consuming process, but I find it's best to delay my initial enthusiasm for a story. To dam up the enthusiasm so that it starts to overflow. These notes can come from anywhere. I pick my reading pre-novel quite carefully. Poems I find are the best place, as they're quick and easy to skim through as I'm looking for phrases or sentences or descriptions that excite me. For Hastings, my forthcoming sequel to Shieldwall, I came across the Nobel Prize winning Swedish poet, Tomas Transtromer, and found many details of a Scandinavian landscape that would have been familiar to many of my characters. At the same time I might be using details that I've picked up from Sagas, or something more left field, like one of the Tang Dynasty poets, whose laments for China during invasions from the steppes, were fertile ground for gleaning details for Shieldwall, which covers a similar time in English history.

And even though these Tang Dynasty poets are divided from Dark Age England by thousands of miles, in many ways they lived in similar worlds, divided by distance but not by time: so many of the basic details of common day life would be more familiar to an Anglo Saxon or a Viking than they are to the modern reader.

Often the story starts to develop as I'm thumbing through old notes. Sparks start to fly. Connections begin to form, and I learn things about my characters and about the challenges they face from the notes that I have gleaned. I think this is natural. The reason the phrases first excited me is because they spark something within my mind. And its from the same dark reaches of the sub conscious that the stories come back out again.

I keep these index cards in a drawer: and they're roughly divided between those that are only relevant to the modern world (advertising slogans, and DO NOT WALK ON THE GRASS signs etc) and all the others. When I start a project, I sit down and go through them and pick out ones that speak to me and this particular story.

Then I pin them onto the wall, and surround myself with all these little bits of a story. They're like salvaged pieces from an enormous and mostly lost jigsaw puzzle, blutacked up all over my room. It's my job to find the right place for them within the 'picture'.

Eventually the day comes when you have to start writing. And here comes the practical bit. You remember the cards that sparked ideas - and look over all the overs. Some will speak to you, others will not. Some will claim a place within the scene you are about to write. I take all these and pin them up above my screen. And these are then the stepping stones for the scene ahead of me.

Because they are scraps that have come from so many places, they add a broad depth of detail or register to your writing. You can play around with them, by limiting yourself to only using notes from certain sources for various characters, which brings a subtle change of voice for each character. What you can do with this process is almost limitless. And you don't need to limit yourself to index cards and language. You can use pictures instead!

Sunday, January 8, 2012

Dave Hughes, In Memoriam

In Praise of English Teachers

At the end of last year my old English teacher, Dave Hughes, died. I saw him last in the summer, when he came to my book signing in York, and admonished me for repeating words in the opening scenes of Shieldwall.

'It's meant to be poetic repetition,' I told him, but he wasn't convinced, and I think he was still marking me down.

We were supposed to go for a coffee, but he seemed distracted, and hurried off. I only found out later that he was suffering from bowel cancer, and that in five months he would be dead.

I meant to write personally to him, but in the end, his death came quicker than my letter, and all that arrived in time was a Facebook message. Less than I had intended, but then so much in life is so. But fitting perhaps, that it was on Facebook that he chronicled his decline.

His Facebook page is still there. I wonder how long it'll be before Facebook decide his account has been inactive for too long, and they clear away his account.

I was 13, in grade 3 at St Peter's School, York, when Dave became my English teacher, and he remained it, and I kept the same seat in the same class until I left school at 18. We went through 'O' levels and 'A' levels together: namely, the Miller's Tale, Auden's poetry, Macbeth, Hamlet, Douglas Dunn, and Rosencrantz and Guildernstern and Dead.

Dave was the kind of teacher who had something of the Dead Poet's Society about him, before the film or the concept came out. We called him Dave, rather than Sir. He had a curriculum in mini lessons that he gave to you at the beginning of term, and included his and other student's writings. He liked to recite chunks of the Canterbury Tales in middle English, and invited us to write modern versions: the Tax Collector's Tale; the Hairdresser's Tale; the Policeman's Tale. Before we were old enough to pass as 18, he used to invite me and a few friends over to his house on a Saturday night, and we sat in his living room, like juvenile Inklings, with our cans of John Smiths by our feet, and he talked to us as if we had something interesting worth saying.

That first lesson he taught us about speed reading, and let us ask him any questions we liked: and he answered them all. Though letting a class of 13 year old boys come up with questions was always inviting a degree of silliness.

There was a lot of distinctive things about Dave. He handed back your work with a sheet of footnotes on your work. These could run into 30s little numbered stars, with comments on a separate sheet. I remember the day he gave a short story I wrote, 36/40. Anything about 34 was great, 35 fabulous, and that 36 earned me a distinction in English, and a little early confirmation that I might have a gift.

I told him, or perhaps my parents did at parents night, that I both loved Tolkien and wanted to be an author. Both seemed embarrassing details at the time. But Dave was kind and considerate, and I think he shared my love of Northern literature. He was of course, drawn to mountains, and tragically to Norway, where his friend, and my chemistry teacher, died in a climbing accident on the Svartisen Icecap, in Arctic Norway in 1986. And he had poems published in a journal called Giant Steps, alongside names now well known, like Simon Armitage and Helen Dunmore. My first signed book: and knowing an author seemed such an important step towards becoming one myself.

Even though I now have many other signed copies - from more renowned authors - Dave's collection of poems keeps it's prized place.

And this morning as I brought it down, I found tucked inside a bundle of his curriculum, with the distinctive typeface he used.

It was odd reading his Facebook posts. He had a gift for language of course, but the most poignant thing Dave wrote on his Facebook account, was 26th October.

NOT a good week so far... Felt terribly weak - and had to abandon a stay with Mum and Dad when reflections of each other other simply made us aware of what each side was losing. I rode the stair-lift and Dad could only say, this was meant for me, not for you.

But feeling better: if I can have another transfusion, it could make all the difference. Do call soon if you plan to call at all....

And when a friend promised to visit after Christmas, he wrote:

David Hughes: won't be here till then, Sorry

But rather than these as his last words, perhaps better would be his poem Valediction, for his friend Barry Daniels, who died attempting to save a student who had fallen into a crevasse. I think much of this would apply equally well to Dave:

You'd much prefer a place where gods might hike

on sponsored walks that you could organise -

to build a climbing wall, or something like.

Your sort of heaven should have lowering skies

that always look like rain, but never quite

make up their minds - then soak you by surprise

and leave you squelching in your tent all night

with sodden sleeping bag and wrinkled feet,

damp boots, wet breeches, shrinking till they're tight.

When morning hammers in with wind and sleet,

disgusting though it seems, your flapping tent

must feel a bit like heaven: twelve square feet

comparatively dry, where you're content

to fester till they call you. Then in haste

you'll shudder into clothes: it's time you went.

I hope your lunch is always Lion Bar waste

or greenfruit pastilles - nowhere near a stream

to swill away their sickly after-taste

It don't take much of those to make it seem

that reindeer pate, marmalade and bread

are things you've never eaten, just a dream.

But dreams aren't thinks confined to food or bed:

your waking, walking dreams inspired us all

to want to follow paths you chose and led -

and led us safely till your own one fall,

your fatal stumble where our paths all fork.

I mostly hope your heaven holds lands that call

where all their better bits are three months walk

through glaciated valleys, peak on peak,

that shadow, loom, and avalanche; and talk

must always plan in detail, week by week,

the many first ascents that wait for you:

those marvellous, untrod summits you still seek.

NB

After posting this I went in search of some of Dave's poems, but came across this instead, which says a lot about what a distinctive man Dave was.

At the end of last year my old English teacher, Dave Hughes, died. I saw him last in the summer, when he came to my book signing in York, and admonished me for repeating words in the opening scenes of Shieldwall.

'It's meant to be poetic repetition,' I told him, but he wasn't convinced, and I think he was still marking me down.

We were supposed to go for a coffee, but he seemed distracted, and hurried off. I only found out later that he was suffering from bowel cancer, and that in five months he would be dead.

I meant to write personally to him, but in the end, his death came quicker than my letter, and all that arrived in time was a Facebook message. Less than I had intended, but then so much in life is so. But fitting perhaps, that it was on Facebook that he chronicled his decline.

His Facebook page is still there. I wonder how long it'll be before Facebook decide his account has been inactive for too long, and they clear away his account.

I was 13, in grade 3 at St Peter's School, York, when Dave became my English teacher, and he remained it, and I kept the same seat in the same class until I left school at 18. We went through 'O' levels and 'A' levels together: namely, the Miller's Tale, Auden's poetry, Macbeth, Hamlet, Douglas Dunn, and Rosencrantz and Guildernstern and Dead.

Dave was the kind of teacher who had something of the Dead Poet's Society about him, before the film or the concept came out. We called him Dave, rather than Sir. He had a curriculum in mini lessons that he gave to you at the beginning of term, and included his and other student's writings. He liked to recite chunks of the Canterbury Tales in middle English, and invited us to write modern versions: the Tax Collector's Tale; the Hairdresser's Tale; the Policeman's Tale. Before we were old enough to pass as 18, he used to invite me and a few friends over to his house on a Saturday night, and we sat in his living room, like juvenile Inklings, with our cans of John Smiths by our feet, and he talked to us as if we had something interesting worth saying.

That first lesson he taught us about speed reading, and let us ask him any questions we liked: and he answered them all. Though letting a class of 13 year old boys come up with questions was always inviting a degree of silliness.

There was a lot of distinctive things about Dave. He handed back your work with a sheet of footnotes on your work. These could run into 30s little numbered stars, with comments on a separate sheet. I remember the day he gave a short story I wrote, 36/40. Anything about 34 was great, 35 fabulous, and that 36 earned me a distinction in English, and a little early confirmation that I might have a gift.

I told him, or perhaps my parents did at parents night, that I both loved Tolkien and wanted to be an author. Both seemed embarrassing details at the time. But Dave was kind and considerate, and I think he shared my love of Northern literature. He was of course, drawn to mountains, and tragically to Norway, where his friend, and my chemistry teacher, died in a climbing accident on the Svartisen Icecap, in Arctic Norway in 1986. And he had poems published in a journal called Giant Steps, alongside names now well known, like Simon Armitage and Helen Dunmore. My first signed book: and knowing an author seemed such an important step towards becoming one myself.

Even though I now have many other signed copies - from more renowned authors - Dave's collection of poems keeps it's prized place.

And this morning as I brought it down, I found tucked inside a bundle of his curriculum, with the distinctive typeface he used.

It was odd reading his Facebook posts. He had a gift for language of course, but the most poignant thing Dave wrote on his Facebook account, was 26th October.

NOT a good week so far... Felt terribly weak - and had to abandon a stay with Mum and Dad when reflections of each other other simply made us aware of what each side was losing. I rode the stair-lift and Dad could only say, this was meant for me, not for you.

But feeling better: if I can have another transfusion, it could make all the difference. Do call soon if you plan to call at all....

And when a friend promised to visit after Christmas, he wrote:

David Hughes: won't be here till then, Sorry

But rather than these as his last words, perhaps better would be his poem Valediction, for his friend Barry Daniels, who died attempting to save a student who had fallen into a crevasse. I think much of this would apply equally well to Dave:

You'd much prefer a place where gods might hike

on sponsored walks that you could organise -

to build a climbing wall, or something like.

Your sort of heaven should have lowering skies

that always look like rain, but never quite

make up their minds - then soak you by surprise

and leave you squelching in your tent all night

with sodden sleeping bag and wrinkled feet,

damp boots, wet breeches, shrinking till they're tight.

When morning hammers in with wind and sleet,

disgusting though it seems, your flapping tent

must feel a bit like heaven: twelve square feet

comparatively dry, where you're content

to fester till they call you. Then in haste

you'll shudder into clothes: it's time you went.

I hope your lunch is always Lion Bar waste

or greenfruit pastilles - nowhere near a stream

to swill away their sickly after-taste

It don't take much of those to make it seem

that reindeer pate, marmalade and bread

are things you've never eaten, just a dream.

But dreams aren't thinks confined to food or bed:

your waking, walking dreams inspired us all

to want to follow paths you chose and led -

and led us safely till your own one fall,

your fatal stumble where our paths all fork.

I mostly hope your heaven holds lands that call

where all their better bits are three months walk

through glaciated valleys, peak on peak,

that shadow, loom, and avalanche; and talk

must always plan in detail, week by week,

the many first ascents that wait for you:

those marvellous, untrod summits you still seek.

NB

After posting this I went in search of some of Dave's poems, but came across this instead, which says a lot about what a distinctive man Dave was.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)