Thursday, May 10, 2012

How to Write a Medieval Novel: a practical guide no. 2

So! you're characters are riding through the countryside, or they come out of their doorways - and.... what do they see?

Good stories, where ever they're set need worlds that are believable and often it's the variety and authenticity of the little details that really lift historical fiction, and give the reader the illusion that they've immersed themselves in a real world in all its facets: with farmers, clerics, travellers, pilgrims, knights or huscarls all mingling in a way that feels real.

Of course no one has been to the Middle Ages, so how do you bring this level of detail to your story?

The written sources tend to be a little bland on these little everyday details for almost any period because chroniclers don't see much noteworthy in the 'everyday.'

There are a few places where you can find these details. Aelfric's Colloquys are a good example. Fancy catching a whale today lads?! Check out Ann E. Watkin's translation here

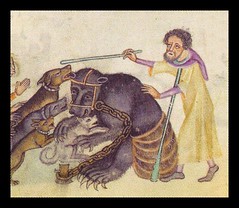

But luckily the monks who illustrated thier texts seem to have had a penchant for putting the everyday in the margins of the holy, profound, sacred and heroic texts they were illustrating.

Wednesday, May 9, 2012

Have you liked Shieldwall yet?

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Shieldwall-Justin-Hill/dp/0349123373/ref=tmm_pap_title_0?ie=UTF8&qid=1315579893&sr=1-2

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

How to write a Medieval Novel: a practical guide no. 1

The Dark Ages?! Not at all. As I'm doing all this again, I thought I would list the things I've found useful in creating a convincing medieval setting.

1. The literature. Duh! In some ways there's nothing better than what contemporaries wrote about the world they lived in. For an Anglo Saxon setting this left me a little stumped, as anyone who's read any Anglo Saxon poetry, knows that the Anglo Saxons lived in a permanent winter, amidst ruins, and lamenting the fate that led them to exile/lordlessness etc. I was left a little stumped, because I couldn't have a novel set in a permanent midwinter. But then I came across this book, The Lost Literature of Medieval England, in the corner of Lingnan University library, which had last been taken out in 1962. A fabulous read, it also introduced me to the corpus of Anglo Saxon literature written in Latin, which composes of hagiographies, which are the opposite of the poetry, in that they chronicle how saints turned cold wilderness into flowering fields full of birds and bounty.

Bingo! I now had contemporary sources chronicling both their of summer and winter.

But of course it's not so straightforward, as writers often wrote because they had ulterior motives. Richard Fletcher is very good in The Barbarian Conversions, in teasing the religious accounts of conversions, where Saint A turned up at pagan site Z, chopped down their sacred oak, and then the people were amazed and accepted Christ. He asks the kind of questions any serious writer should ask: what exactly did that mean? How well did people understand what they were accepting. How much did older beliefs survive and continue in different forms. I find it's always good to remember that just because people lived in a less enlightened age, they were not necessarily any more or less daft than people now. And in many ways their concerns might prove surprisingly similar to worries now.

Take the Anglo Saxon charms, for example. Often they say put a poultice on and say a certain prayer or charm three times. Now the simple reading would be that they believed in the power of mystical charms. Or - and perhaps a more practical and interesting explanation is that the repeating the charm five times took a certain and appropriate amount of time. Something of an ancient egg charmer.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)